Florida farmers struggle as legal foreign workers worry about immigration crackdown

Published in Business News

Joel Trejo’s American Dream may be in jeopardy.

At 15, Trejo emigrated from Mexico to the U.S. to work at a citrus nursery in Florida. After a few years as an employee, he decided to launch his own company, selling citrus trees grown out of his sprawling 80-acre backyard in Lake County, Florida, not only to his former employer but also to big box stores like Walmart and Lowes.

But now, despite hiring legal workers under the H-2A visa program, he’s struggling to find labor amid the U.S. crackdown on illegal immigration.

Even agriculture workers who enter the U.S. legally, doing jobs Americans find undesirable, are fearful of being targeted by federal enforcement efforts and have chosen not to come, advocates and experts in the field say.

“I’ve never seen it like this before, and out of all the struggles in the citrus industry this is probably the biggest one,” Trejo said. “It’s going to get worse if nothing gets done, and we’re going to pay the price.”

A long and bureaucratic process

By the numbers, Florida’s agriculture industry may be the most at risk in the current squeeze, out of all 50 states.

While most foreign-born agricultural workers in the U.S. are believed to be in the country illegally, foreign workers can live here and work legally on farms for a period of up to three years if they follow the strictures of the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers program.

Florida has had the largest number of H-2A workers in the country in recent years, according to the departments of State and Labor, with nearly 52,000 certified positions out of the roughly 310,000 H-2A visas that were issued in 2023. Data for 2024 is not yet available.

The H-2A process, which involves three different federal agencies, requires an employer to file a certification with the Department of Labor, which ensures there aren’t enough workers domestically to fill particular positions. Then a visa petition is filed with the Department of Homeland Security.

Workers are vetted through consulate appointments in their home country and, once approved, can make their way to a U.S. farm to work.

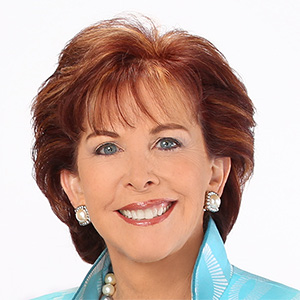

The process is long and bureaucratic, so farmers often hire a consulting firm to help. Chris Ball, CEO of másLabor, one of the nation’s largest recruiting firms, said the company brings in tens of thousands of workers, the majority from Mexico, to farms across the country but mostly in Florida.

On Thursday, two new policies took effect that should streamline the H-2A program, including allowing partially online applications for the first time — checks and documents would often get lost in the mail, Ball said — and revising how H-2A hourly rates are determined.

Ball said the changes should help speed up the tedious process that can take anywhere from 60 to 100 days. But he is skeptical it will be enough.

“The Trump administration has said that they want to make agricultural visas easier because they contend that one of the largest illegal immigration populations in America is on the farm,” Ball said. “But a lot of times, government’s intention and what actually happens are two different things.”

Still, the most difficult part is the cost.

Farmers must pay roughly $2,000 to $4,000 for each employee to the firm and in fees associated with the program, Ball said. Smaller farms often don’t have the margins to afford those costs, one reason undocumented workers may be hired instead.

The crackdown on illegal immigration has encouraged U.S. farms to seek more H-2A visa employees, Ball said. But it’s had the opposite effect on the supply of legal ag workers. Ball says his recruiting firms in Mexico have seen a slight dip in people applying to work in the U.S.

“It’s been positive for our business, because now people are like, ‘I have to do this the right way and I can’t hire illegally’,” Ball said. “But the people in Mexico … they’re asking if it’s safe. ‘Am I going to get deported?'”

‘You don’t know if they’re going to make it home’

The future of the Trejo family farm — Joel works with his son Danny — is in peril if things don’t improve. Already Joel is logging 10- to 12-hour days, he says.

“It’s grown to the point where I cannot handle all the work myself,” Joel Trejo said. “I can find people, but I also don’t want to put anyone at risk because there are people being deported even with proper documentation. Every time they come or leave it’s worrisome, and you don’t know if they’re going to make it back home. I would feel like it’s my fault.”

Just a couple of years ago, Trejo said he had around 20 employees helping him. But now he’s afraid to request those same workers over fear of putting them in harm’s way.

The mounting pressure on the agriculture industry led to President Trump seemingly offering a reprieve in June, saying at a White House event, “Our farmers are being hurt badly and we’re going to have to do something about that.”

Later that week, the administration sent internal memos pausing ICE raids on farms and other industries that rely on undocumented workers. But just days later, the policy was rescinded.

No meaningful action has come since, and the immigrant community has been left unsure of what its future holds.

The másLabor firm created an app allowing workers to display paperwork showing they’re here legally, but at times even that precaution has failed. During the spring, as the season began, numerous immigrants had their documents scrutinized and some were even deported or arrested by ICE, Ball said.

“We had a couple people sent home by mistake,” Ball said. “We had people stopped and arrested and then once they got their paperwork in order they were [let go].”

The H-2A visa is supposed to keep immigrants safe from arrest by ICE. But Yesica Ramirez, general coordinator with The Farmworker Association of Florida, said she’s also seen cases of people with these permits getting arrested.

“The fear is here, and it gets back to the country of origin of the families here too through the news and just staying in touch,” Ramirez said in Spanish. “They have a credible reason to be afraid.”

The father-son Trejo duo recently expanded their e-commerce company Via Citrus, where people can buy an orange or lemon tree from Amazon or Etsy, to 10 acres in Apopka. But its future remains unclear.

“We may have to reduce our acreage because it takes a certain amount of people to maintain it,” Trejo said. “We just don’t know.”

©2025 Orlando Sentinel. Visit at orlandosentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments