Watershed moment for San Diego's minimum wage in 2026. Which workers benefit the most

Published in Business News

It was just a couple of years ago that the minimum wage landscape in California reached a major milestone — fast food workers would begin earning $20 an hour, a monumental boost in pay over the state’s then hourly rate of $16. It would set a new bar for service workers up and down the state.

That bar is changing yet again, but this time in San Diego, where later this year, a sizable share of the city’s lowest paid workers will be celebrating an even bigger watershed moment — the first phase of what will eventually be a $25-an-hour minimum wage reserved for thousands of tourism industry employees who work at hotels, amusement parks and event centers like Petco Park and Snapdragon Stadium.

While the citywide minimum wage will rise a modest 3% to $17.75 on the first day of the new year, it will easily be eclipsed six months later by a $19 hourly wage for hotel and theme park workers and $21.06 for those employed by event centers. By 2030, when the $25 hourly rate goes into effect for all hospitality workers covered by the new wage law, they will have seen their pay jump by as much as 40%.

Outside the city of San Diego, the new minimum wage in the county will rise to $16.90 an hour on Thursday, the same rate as what is mandated in the state.

San Diego businesses, chief among them hotels, are girding for significantly larger labor costs that they say could translate to higher charges for guests and a contraction in operating hours of bars and restaurants. And restaurant owners, who are not covered by the tourism wage, say it will undoubtedly have a ripple effect that will likely force them to similarly boost pay for their employees.

“This is just another way the City Council is making it more expensive to live in San Diego — water, trash, parking, and now this, which will increase the cost of dining, shopping and entertainment,” said Robert Gleason, who chairs the San Diego County Lodging Association and is president of the locally based Evans Hotels. “We all compete for the same workers, so while this has a direct impact on tourism and event center workers, it will have an indirect inflationary impact on all wages and therefore, the cost of everything in San Diego.”

Workers, meanwhile, are welcoming the arrival of the new mandated wage, but at the same time lament that it’s still not nearly enough to live on when a single person raising one child in San Diego County would need to earn more than $53 an hour working 40 hours a week to adequately support themselves, according to a “living wage” calculation produced by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

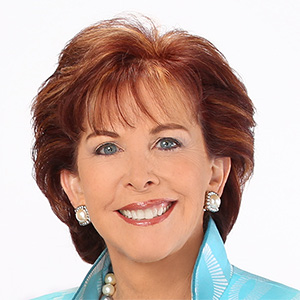

“It is very hard because everything is so expensive,” said Samara Talavera, 56, a housekeeping supervisor at the Handlery Hotel in Mission Valley, where she currently earns $19.52 an hour under a union contract. She lives in a rented two-bedroom house near Logan Heights with her 17-year-old granddaughter, whom she supports. “I just received an email from San Diego Gas and Electric that prices are going up, so it is hard for me. I can’t buy clothes, go out for dinner, go on vacations.”

Nonetheless, the incremental increases in the tourism wage will be increasingly meaningful, she said, especially for those workers who are not earning union wages.

“It’s important because little by little we are going to get more money,” Talavera said. “If we didn’t have this law, we would have felt hopeless, like it would never get better.”

Unions push for industry-specific minimum wages

Even though the city of San Diego’s minimum wage has largely kept pace with other California cities that have raised hourly rates above what is mandated by the state, there’s a growing trend in the labor movement to push for industry-specific hourly wages with still higher minimums. That’s already the case with fast food workers, certain health care employees, and now tourism workers. In Los Angeles, the city approved a new minimum wage last year that is scheduled to reach $30 an hour by 2028 and applies to hotel and airport workers.

San Diego’s new wage law specifically applies to a few categories of employers — hotels with 150 or more rooms; amusement parks, which will only affect SeaWorld; and event centers, which encompass a variety of hourly workers employed at Petco Park, Pechanga Arena San Diego, the San Diego Convention Centeron and the Civic Theatre.

In the case of hotels and SeaWorld, the new wage floor will start at $19 an hour on July 1 and increase each year by $1.50 until it reaches $25 in 2030. San Diego officials say there are 89 hotels in the city with at least 150 guest rooms, and those properties account for more than 27,000 rooms. For event centers, the July 1 rate will be $21.06, with yearly wages going up by a dollar a year until 2030.

The July 1 increase comes against the backdrop of a steady growth in the citywide minimum wage, which has jumped 60% in the past decade.

It should be noted that several San Diego union workers who are covered by the tourism wage ordinance already earn well over $21 an hour. Among them are janitorial and event set-up workers at the Convention Center, housekeepers in downtown San Diego hotels, and audiovisual technicians who staff hotel meetings and conferences.

Local union leaders stress that, despite those higher-level wages, the new tourism wage is no less consequential.

“We’re saying we have to raise the wage floor for everyone and yes, it’s sometimes a slow and tedious process,” said Christian Ramirez, vice president and political director for SEIU United Service Workers West. “But ultimately the goal has to be to bring wages up for workers across San Diego and the state that reflect how expensive it is to live here.

“And this will also help the janitorial workers at Petco Park and signal to other industries that if hospitality has done this, other industries should do it. There are a lot of janitors who work at biotech companies, and they’re barely making above 20 bucks an hour.”

Many hotels and restaurants in San Diego County also pay their non-tipped employees significantly more than the current minimum wage, in large part because of the need to attract in-demand workers post-pandemic. Owners, however, say they fear they will have to pay still more once the tourism wage goes into effect, as it will put more pressure on them to maintain a healthy pay gap between entry-level and more experienced workers.

Hotels worry they’ll be at a competitive disadvantage

Richard Bartell, president of San Diego-based Bartell Hotels, said his biggest concern is absorbing the increase for his tipped employees, who already make at least $30 or more, including tips. Bartell has eight San Diego hotels ranging in size from 73 to 292 rooms. The chain employs some 900 workers, about 20% of whom are tipped, he says.

“I understand that there was no legal way to exclude the tipped employees, but we have restaurants that compete with non-hotel restaurants in San Diego, so it puts hotels at a competitive disadvantage with every other restaurant where the workers don’t make $25 an hour,” Bartell said.

“The increase will also put a lot of pressure on us to operate more efficiently. Do we need a hostess or can the manager do that or can servers fulfill the role of a busser? So will we have to reduce hours, shifts? I think consumers will see a price hike because restaurants in hotels will be forced to raise prices, but we will have to be careful to not raise prices too much.”

When the plan to boost the pay of tourism workers was first publicly aired in early 2025, Councilmember Sean Elo-Rivera, who initiated the proposal, dismissed claims from critics that prices would rise, and San Diegans would bear the brunt of the higher wages.

The Padres, early on, implored the mayor and City Council to remove Petco Park from the tourism wage mandate, arguing that the team is already subject to the city’s living wage ordinance, which imposes a higher wage floor than the citywide minimum wage. Without such an exemption, the team argued, the eventual $25-an-hour wage would increase the team’s operational costs that would be felt, “first and foremost by San Diegans in the form of increased food, beverage and ticket prices.”

The Padres have yet to indicate whether the higher wage could lead to fans paying more at the ballpark, but an emailed statement sent last week to the Union-Tribune suggested that such an outcome remains a possibility.

“The Padres already paid the highest mandated minimum wage in Major League Baseball prior to the passage of this ordinance, which will push that wage even higher,” the team said. “At a time when visitor activity in San Diego is declining, event-driven activity at Petco Park directly affects shared revenues with the City, making competitiveness an important consideration. Also, given San Diego’s high cost of living, policies like this put further financial pressure on San Diegans when attending Padres games and other events at Petco Park. As the ordinance is phased in, we will evaluate operational impacts and make adjustments as necessary.”

What do economists say?

The potential consequences of rapidly rising minimum wages, from job losses to higher consumer costs, have been fodder for economic analyses over the years, but there isn’t always consensus about what happens when hourly wages take a big jump.

A December news release from the Economic Policies Institute, a fiscally conservative think thank with some ties to the restaurant and hotel industries, highlighted a soon-to-be-published study that concluded that “steep wage hikes kill jobs, reduce employment opportunities, and shutter businesses.” More specifically, it claims that large minimum wage changes from 2011 to 2019 led to a decline in the employment rate of 2.65 percentage points.

University of California-Berkeley economics professor Michael Reich, who has studied the minimum wage issue extensively, takes issue with the Economics Policies Institute, which he describes as producing “specious hit pieces on minimum wages.”

Reich, who chairs Berkeley’s Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, researched the effects of the 25% fast food minimum wage boost that went into effect in April 2024. The study took into consideration that some fast food workers were already earning more than the statewide minimum wage, meaning that not all such employees received a 25% hourly wage hike.

Drawing on Census data that show labor costs represent about 30% of a fast food restaurant’s operating expenses, Reich and his co-author calculated that the wage increase could be fully absorbed by a price increase of about 3.3%, without sacrificing any profits.

Relying on data they collected from UberEats in California and in states that did not raise their minimum wage, they found that prices at fast food restaurants in fact rose by just 2.1%. In other words, there was only a partial pass-through of higher labor costs to customers, said Reich.

“Many labor economists believe employers set wages too low to attract the workers they need, so there’s a high turnover rate,” he said. “And when wages go up, we see turnover go down. It’s not that they kill jobs but rather, job vacancies.

“There’s always a lot of fears thrown up, that costs are going to go up by double digits, but when you look at the data, it just doesn’t work out that way. And employers often don’t take into account that turnover is going to go down because when wages go up, we do see turnover going down. So employers are going to save a lot of turnover costs.”

Unite Here Local 30 President Brigette Browning, whose union represents hotel workers, minces no words when she hears employers raising the specter of higher prices for consumers.

“Why can’t they make just a little less money?” she said. “They’ll raise the prices anyway if they think the people will pay for it. It’s not because they’re paying a little more to their workers. It’s because they think they’ll reap bigger profits.”

Julian Hakim, co-owner of the San Diego-based Taco Stand chain, recognizes that while the tourism wage doesn’t apply to his business, there’s no doubt it could still have a ripple effect on employers like him, he says. His taquerias have not seen a price hike in a couple of years, and he’s likely to keep it that way, but he says that could change as other hospitality worker wages continue to rise more quickly.

“Having spoken with a lot of my colleagues where everyone is living through tighter (profit) margins as labor costs go up, it will trickle down to the consumer,” he said, “It has to. A lot of restaurant owners have jumped the gun and already done it. It’s ultimately the consumer that takes the brunt of it. I don’t think this is the solution, to just keep raising the wage, but it’s the easiest one for politicians to use and so they keep using it.

“Fortunately, we are busy, and our employees can make extra money from tips, so it may outweigh them going somewhere else that pays higher. We’re in for the ride.”

©2025 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments