Boeing beats Airbus on orders, still behind on production

Published in Business News

Boeing booked more orders in 2025 than its European rival, but Airbus continued to produce more planes than Boeing for the seventh year in a row.

Boeing had one of its most successful years since 2018, before two fatal 737 MAX crashes, the COVID-19 pandemic and, in 2024, a midair blowout and two-month Machinists strike upended the manufacturer’s operations.

Last year, Boeing booked 1,173 net orders, a massive increase from the 377 net orders it recorded in 2024 and the fifth-highest annual count in Boeing’s history.

The manufacturer delivered 600 airplanes in 2025, up from the 348 delivered the year prior and its highest annual delivery total since 2018, when it delivered 806 airplanes.

Airbus, meanwhile, delivered 793 planes in 2025, up 4% from the 766 aircraft it delivered in 2024. Airbus booked 889 net orders last year, compared with 826 the year prior.

In October, the A320 family surpassed Boeing’s 737 as the most-delivered commercial plane in history.

But late last year, the A320, which competes with the 737, faced two disruptions.

In November, amid the busy Thanksgiving travel season, Airbus identified a software issue on the single-aisle plane. It found that “intense solar radiation” may “corrupt” critical flight control data, requiring modifications to about 4,000 planes already in service.

Then, in December, Airbus discovered a supplier quality issue on panels that make up the A320 forward fuselage, requiring heavy inspections and slowing production of the manufacturer’s most popular plane. Airbus lowered its delivery target for the year from 820 aircraft to about 790 planes in December.

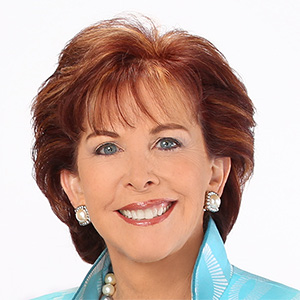

Christian Scherer, the outgoing CEO of Airbus commercial aircraft, said at a news conference Monday that those issues won’t carry into 2026.

He acknowledged that Airbus still faced supply chain constraints, primarily around the availability of engines. But “the overall situation … is much brighter now,” Scherer said from Airbus’ Hamburg, Germany, production facility.

Boeing, meanwhile, celebrated a year of increased production for the 737 MAX and its 787 Dreamliner, the twin-aisle plane it produces in North Charleston, S.C.

In December, Boeing delivered 45 737s and 14 787s, its highest monthly delivery total for both programs in 2025. Deliveries are not directly comparable to production rate, but the numbers can provide a proxy for how quickly Boeing is moving aircraft through its production line.

The Federal Aviation Administration in October lifted a production cap on Boeing’s 737 MAX that it had in place since the midair panel blowout in January 2024, allowing Boeing to increase monthly production from 38 to 42.

Boeing plans to continue increasing 737 monthly production in similar increments, with about six months between each rate hike, though CEO Kelly Ortberg stressed Boeing will not ramp up until it has met metrics designed to maintain safety and quality.

In another vote of confidence, the FAA granted Boeing permission last year to help certify when planes are ready to fly, an authority the regulator revoked after the two fatal 737 MAX crashes in 2018 and 2019.

Much of Boeing’s focus this year will be on achieving long-delayed FAA certification for new plane models, including two MAX variants and the 777X family. The delays have left a gap in the market, allowing Airbus to promote its largest widebody, the A350-1000, without a competitor until the 777X is ready to fly with passengers.

Both manufacturers celebrated their widebody order book at the end of 2025.

Airbus said Monday that airlines are turning to the A330 and A350 to replace their existing fleet of Boeing widebody planes. Airbus booked 265 widebody orders last year.

Boeing ended the year with 368 orders for the Dreamliner, its highest annual order total since 2007, when it completed final assembly for the first 787 and recorded 369 orders. Boeing also booked 158 orders for its yet-to-be-certified 777X from January through November last year.

Many of Boeing’s orders coincided with President Donald Trump’s visits with international leaders or came amid Trump’s threats to impose steep tariffs on countries where he felt there was a trade imbalance. By the end of the year, politicians were calling Trump the manufacturer's best salesman.

On Monday, Scherer said Airbus wasn’t intimidated by Boeing’s political power. Instead, it was an incentive.

“It’s undeniable that Boeing benefited from political backing,” Scherer said. “What it means for us is that we just have to be more convincing than our competitor and its political support on the quality of our products, our people, our professionalism.

“It’s actually quite motivating to see Boeing back in the major league after so many years,” Scherer said. “It’s a good thing, this competition, it’s going to make us even more aggressive.”

Production ramp-ups

In 2025, Airbus delivered 93 A220s, its smallest narrowbody plane, which doesn’t have a direct competitor from Boeing. It delivered 607 A320 family aircraft, which includes the A319, A320 and A321.

Boeing delivered 440 737 MAX planes in 2025 and seven 737 NG models, which typically go to Boeing’s defense unit to form the base of the P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft.

Just as Boeing plans to ramp production of the 737 MAX, Airbus hopes to increase monthly A320 production to 75 by 2027.

To do so, it opened two new A320 final assembly lines last year, one in China and one in Mobile, Ala., and a new facility for the A321XLR, which can fly farther than the rest of the A320 family aircraft.

Benoît de Saint-Exupéry, executive vice president of sales for Airbus commercial aircraft, said the A321XLR “fully spread its wings” in 2025 with five new operators. About half of the routes airlines are flying with the long-range aircraft are new routes most narrowbody planes couldn't fly.

Airbus continues to have an issue securing engines from Pratt & Whitney, which produces the geared turbofan engine for the A320.

At the height of the engine delays, Airbus had 60 nearly finished planes stuck in production waiting on engines, something Airbus calls a “glider.” Scherer declined to say how many gliders Airbus currently has but said it is a “very manageable number right now.”

Still, Scherer said the engine issue did not prevent Airbus from hitting its delivery targets in 2025. He placed the blame for that squarely on the A320 fuselage panel quality issue. Had that not happened, Scherer said, Airbus would have hit its original goal of delivering 820 planes last year.

On the widebody front, Airbus delivered 93 twin-aisle planes in 2025 while Boeing delivered 88 787 Dreamliners.

Boeing broke ground in November on a $1 billion expansion of its 787 production campus in North Charleston. The project will add a second final assembly building and 1.2 million square feet to Boeing’s existing footprint, enabling the company to go beyond its goal of 10 787s per month.

Asked how Airbus would respond to Boeing’s expansion, Scherer said he would give only his personal opinion. There was more demand for the A350 than Airbus' current monthly production ambitions, he said.

Setting ambitious targets

In his last news conference as Airbus’ head of commercial airplanes, Scherer faced tough questions about the company missing its delivery target for three of the past four years.

Scherer, who is preparing to hand the reins to Lars Wagner, a former executive at MTU Aero Engines, said Monday he wouldn’t characterize the missed targets as a failure. To him, it’s a sign of ambition.

“I’d rather be on the ambitious side because the demand for our products is so strong,” Scherer said. “We like to plan for what we’d like to commit to our customers, and then things happen.”

Airbus confronted a “very, very wide spectrum of issues,” he continued, and still was close to its delivery window. That’s “more of an encouraging measure of success than failure,” he said.

Boeing, meanwhile, underwent its own leadership transition in 2024, and is now focused on increasing production rates for its existing planes and finalizing certifications for new variants.

It also will spend the year reintegrating supplier Spirit AeroSystems into its fold, after finalizing an agreement to acquire the troubled supplier last year. Boeing and Airbus carved up the parts of Spirit that produce airplane components for each manufacturer, allowing each company to have more control of production quality and pace.

On Tuesday, Boeing announced two orders to start 2026. Delta Air Lines placed an order for 30 787s, with the option to add 30 more, and lessor Aviation Capital Group ordered 50 737 MAXs.

Alaska Airlines announced an order last week for 105 MAXs and five 787s, the largest order in the airline's history. Alaska and Boeing finalized the order in December, so those planes were included in Boeing's 2025 order count.

Scott Hamilton, an aerospace analyst with Leeham News, said in an interview ahead of the yearly results that Boeing may never catch up to Airbus’ production rates — as Boeing ramps up, so too will Airbus.

But he’s not sure that matters in the long run. Boeing can still make a lot of money in the No. 2 slot and there’s plenty of demand from carriers who need two major manufacturers, Hamilton said.

The real competition ramps up again when one of the manufacturers designs a new airplane, Hamilton said. Both Boeing and Airbus have reportedly explored new narrowbody designs but executives quelled rumors that those planes would come anytime soon.

When they do, Hamilton said, “at that point, you reset the race to zero.”

_____

©2026 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments