Massive fraud scheme that fleeced thousands of people had ties to Pittsburgh area

Published in News & Features

Before he was freed from prison by President Donald Trump five weeks ago, David Gentile was a power player in the world of private equity companies, amassing a fortune that included car dealerships, waste hauling firms and storage facilities.

The founder of GPB Capital Holdings boasted of the company's ability to invest in thriving businesses, including the purchase of one of the largest car companies in Pennsylvania — the Kenny Ross Auto Group near Pittsburgh — to reap massive profits.

While overseeing the auto giant, which included nine dealerships in the region, GPB bought a waste hauling firm west of Pittsburgh on its way to attracting thousands of investors who were promised 8% returns on their money.

By the time federal prosecutors in New York targeted GPB and accused Gentile and others of siphoning $1.6 billion from the company, the equity firm had fleeced more than 15,000 people in one of the largest criminal cases of its kind, records show.

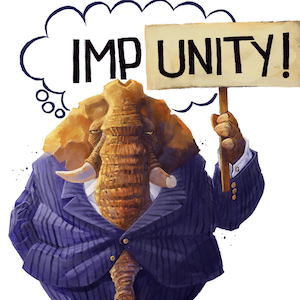

Trump's decision to end Gentile's seven-year sentence in November after he served just 12 days has not only stirred outrage among investors — including veterans, teachers, farmers, and retirees on fixed incomes — but also cast light on the vast assets that GPB purchased to carry out the scheme.

While much has been written about the businesses that were bought by GPB across the country, the Pittsburgh assets and other car dealerships were among the most critical to propping up GPB's claims that it could deliver on its lofty promises to investors.

From the time that GPB bought a majority stake in Kenny Ross in 2017 — a signature brand in the Pittsburgh area for decades — Gentile and others boasted of the role of the dealerships in the success of the company's financial future.

"We focus on income-producing private equity, and Kenny Ross Automotive Group's proven management team and successful track record are great examples of the key acquisition criteria we look for in every deal that we pursue," Gentile said in a news release.

That same year, GPB also bought Iron City Express, a waste hauler in Crescent that would become a part of the private equity firm's portfolio of waste firms that would help attract more investors.

Under GPB's plan, the businesses acquired by the company and its other investments were supposed to generate enough profits to make sure the investors received 8% returns in monthly payouts.

But federal prosecutors say that Gentile and another defendant, Jeffry Schneider, a stockbroker with a troubled regulatory history who helped market the company, lied about the source of the money that was used to keep the dollars flowing to investors between 2015 and 2018.

The company was actually failing to generate enough funds to cover its payouts and began siphoning money from new investors to fill in the shortfalls, while spending millions of dollars to support lavish lifestyles, prosecutors charged.

Gentile, 59, drove a Ferrari FF and flew on a private jet — which included an in-flight attendant — with the expenses covered by investment funds, according to the New York state attorney general's office.

Some of the money he and Schneider paid to themselves was funneled through shell companies while the two men collected nearly $2 million in fees for work for which they were already paid, the attorney general's office said.

Because Trump commuted Gentile's sentence in November after he was convicted of fraud and conspiracy charges in a jury trial, he will no longer be required to pay back investors roughly $15.5 million, according to the grant of clemency.

Schneider, who is still serving a six-year prison term, has asked the trial judge to reduce his sentence, citing Trump's order.

Nick Guiliano, a Philadelphia securities attorney who represents dozens of GPB investors, said the clemency order by Trump was "outrageous" in light of the losses. "People were harmed in this case," he said.

While investors continue to wage legal battles to recover money from Gentile, Schneider and others, the path of the Pittsburgh companies once controlled by GPB took several turns over the past few years.

With increased scrutiny from federal prosecutors in 2019, GPB began breaking up the Kenny Ross group that year — marking the end of an era as an independent brand — and putting individual dealerships up for sale.

When a father-and-son team began angling to buy a Kenny Ross Chevrolet dealership in Somerset, they found it was struggling.

"Financially, (the dealership) was in the red," losing about $500,000 a year, said Andre Palmer, who had run a dealership with his father in Johnstown. "It only had two salespeople. And it had some issues with reputation ... over-promising and under-delivering."

Since buying the business in 2020, Palmer said he has redone the roof, painted the building, improved the delivery area and body shop, and added five salespeople. "We turned it around pretty quickly," he said.

GPB ended up selling four other dealerships still called the Kenny Ross Auto Group in 2021 to Atlantic Coast Automotive of South Florida, one of the country's largest dealership owners. In a Securities and Exchange Commission filing that year, GPB reported it sold those dealerships — two in North Huntingdon and others in Castle Shannon and Adamsburg — for $59.4 million, losing $8.8 million on the sale.

Owners of the other Kenny Ross dealerships did not return calls for comment, but all were sold.

The waste hauler in Crescent took a different path.

After a lawyer was appointed by the federal court in 2021 to monitor the real estate holdings by GPB, a group of investors in Atlanta was contemplating buying Iron City Express, which had about 40 employees.

"There was already a lot out in the news about what was going on with GPB," said Ryan Franco, who, along with his colleagues at Altos Industries, was looking to buy the company located on the banks of the Ohio River.

Franco said their bid was accepted by the monitor, and in May 2022, the paperwork was signed, but a fire later that night swept through the facility that appeared to start from a defective fan and was fueled by tires and other highly flammable materials.

The monitor could have taken the insurance money from the damages and sold off the company's land, trucks and equipment to get all the money that was promised from the sale.

"There was a good chance everyone at Iron City could have lost their jobs," Franco said.

But in the end, the deal moved forward, and eventually new trucks were purchased "to begin doing commercial trash and recycling pickup," said Paul Marker, the CEO for the past year.

The company rebuilt the mechanic shed, bought new tools and made a host of other improvements. As a result, Iron City has added about 10 people to its workforce since Altos bought it three years ago.

Though Gentile is now out of prison, the SEC continues to press a civil case against him, as well as Schneider and two other companies, for rampant violations of federal securities laws.

Toni Caiazzo Neff, a former examiner with the National Association of Securities Dealers, said she detected problems with GPB as far back as 2016 when she was directed by a financial firm to conduct a due diligence review of GPB's investment offerings.

"There were red flags all over the place," said Neff, a suburban Philadelphia resident who later filed a federal whistleblower case.

Based on the company's overall expenses and guaranteed rate of distribution, "the 8% returns were an impossibility," she said. "The minute you see someone guaranteeing 8% returns in the securities industry — you run."

The automotive portfolio of GPB, which included the Kenny Ross dealerships, was "a huge component" that was used to get people to jump into the investment pool, with press releases that created "great fanfare," she said.

Then, turning around and selling the dealerships so rapidly — like the nine Kenny Ross outlets — often at a loss, was further proof that GPB was not a "private equity firm" as it advertised itself, Neff said.

"Private equity looks for companies that are undervalued and can build them up," she said. "That's not what GPB was doing (with car dealerships). They bought them to attract more investors."

Ultimately, the decision by Trump to free Gentile "was an insult to injury to Main Street investors," she said. "These were everyday farmers, nurses. They trusted people. A lot of them lost everything. It runs smack in the face of injustice."

In the wake of the president's action, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said the move was a reaction to a "weaponization of justice" by the Biden administration, arguing that GPB Capital disclosed using investor funds for distributions, making the fraud charges questionable.

Neff said the federal probe of GPB was launched in the first Trump administration in 2019, and that the company was the target of numerous state securities agencies, including those in Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Alabama.

"How many state regulatory agencies went after them for fraud? The grand jury went after them for fraud. The SEC went after them for fraud," she said. "How many have to go after them for fraud to make it a fraud?"

The top federal prosecutor overseeing the case, Joseph Nocella Jr., said in a statement last year that the prison terms imposed on Gentile and Schneider would send a strong message to others perpetrating similar crimes.

"The defendants built GPB Capital on a foundation of lies," said Nocella, who was appointed by Trump. The penalties for both men were "well deserved and should serve as a warning to would-be fraudsters that seeking to get rich by taking advantage of investors gets you only a one-way ticket to jail."

_____

Deputy managing editor for investigations Michael D. Sallah contributed to this report.

_____

©2026 PG Publishing Co. Visit at post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments