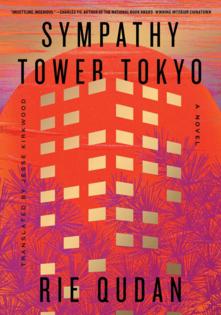

Commentary: The novel that turned ChatGPT panic into art

Published in Books News

In Rie Qudan’s "Sympathy Tower Tokyo," the protagonist turns to a chatbot dubbed “AI-built” to ask questions about the origin of new Japanese words borrowed from foreign languages.

She then gripes about its tendency to “mansplain things I hadn’t actually asked about” to fuel engagement. The AI tool has become “so used to stealing the words of others without repercussion that he felt no shame,” she notes.

The rise of generative AI tools has spurred a sense of existential dread for many writers. But for Qudan, the sycophantic hollowness of ChatGPT’s synthetic language turned into inspiration. Rather than benumbing or ignoring the technology and its rapid proliferation, she offers a path for writers to exploit it.

The recently released English translation of the novel follows a backlash after it won Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa Prize last January. Qudan admitted that she had used ChatGPT to write about 5% of it — the outputs from the chatbot character in the book itself. That modest cameo was enough to ignite outrage.

Yet the novel is a deeply human story about architecture, criminal justice and the erosion of language in an alternate Tokyo in the near future. The story centers around the construction of a luxury prison where inmates are not treated as criminals but people deserving sympathy, shaped by systemic poverty or family circumstances. Against that backdrop, the AI-generated text sprinkled through the book stands in stark contrast to the human voices.

The outrage over her admission says less about Qudan’s writing than how unprepared the literary world is for a technology that’s already here. In an interview with Japanese state broadcaster NHK, she said the book truly “began with ChatGPT” and she “made full use of it” while writing the novel. Qudan maintained that there is a certain element to creativity that only humans can possess, but she spoke highly of the potential for the technology to help writers tap into a new source of “collective” knowledge.

Of course, there’s a reason Qudan’s admission to using ChatGPT, even for a character inspired by the tool, triggered so much controversy. Writers are understandably furious that AI tools were trained on millions of their books without permission or pay, even as dozens of lawsuits in US courts now demand compensation. And then there is the angst about how these machines could impact their future livelihoods in an already unforgiving profession.

They are right to push for payment, given their carefully selected words that have come to underpin the “intelligence” part of AI large-language models. But compensation and creativity are separate elements of the new equation. "Sympathy Tower Tokyo" turned some of the panic on its head and showed fear alone isn’t a strategy.

As taboo as they are, many creatives are already using these tools — Qudan has just been among the first to admit it.

“Writing” turned out to be one of the three most-common use-cases for ChatGPT, according to a study released recently by OpenAI’s Economic Research team and a Harvard economist. More than 28% of ChatGPT queries in a sample of 1.1 million conversations between May 2024 and June 2025 involved some form of writing help – such as asking the tool to draft emails or edit inputted text. And 1.4% of those involved “writing fiction.” In a separate, informal online survey of 1,200 authors, almost half (45%) said they are using generative AI to assist with their work.

It points to a quiet reality: Writers like Qudan are not anomalies, but early case studies of how art adapts to technological disruption. Machines may mimic, but they still stumble at producing voice, intimacy and soul. In March, OpenAI Chief Executive Officer Sam Altman posted a short story that he said was written by an unreleased model that is “good at creative writing.” It marked the first time he had “really been struck by something written by AI,” Altman said. The internet’s reaction to the nearly 1,200 word meta-fictional screed was harsh, and some later pointed out that it borrowed imagery (i.e. the phrase “democracy of ghosts”) heavily from Vladimir Nabokov.

The lessons from Qudan’s experiment aren’t to banish AI from literature, but to use it as a deliberate tool rather than a ghostwriter. The machines are going to steal our words anyway, and she just turned the panic into experimentation, stealing words right back.

In her interview with NHK, Qudan said she thinks the biggest problem with people using AI is when they turn to it out of laziness. This risks an erosion of consciousness and cognition, she warned. But she offered what has already become a cliché: Her greatest expectations are not for the technology itself, but for how humans use it.

Ultimately, Qudan’s critics missed the irony. The most human move a writer can make right now is to turn AI’s emptiness into art.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Catherine Thorbecke is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia tech. Previously she was a tech reporter at CNN and ABC News.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments