Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

Published in Political News

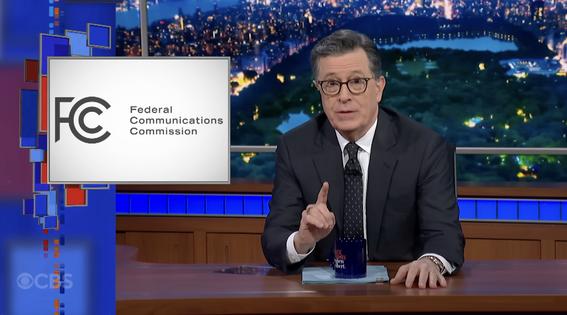

Talk show host Stephen Colbert made headlines on Feb. 17, 2026, when he wrapped a network statement in a dog-waste bag and tossed it in the trash.

He did it live, while on air.

The move came after CBS lawyers reportedly told him he could not broadcast a scheduled interview with Democratic Texas Senate candidate James Talarico on his show, Late Night with Stephen Colbert. According to Colbert, the network warned him that broadcasting the interview could trigger the Federal Communications Commission’s equal time rule, which requires broadcasters to allow political candidates equal access to the nation’s airwaves.

CBS said it gave Colbert “legal guidance” that airing the segment could raise equal time concerns and suggested other options.

Colbert countered that in decades of late-night television, he could not find a single example of the rule being enforced against a talk show interview. He ultimately posted his Talarico interview on YouTube instead, where broadcasting rules don’t apply.

As a media scholar, I believe Colbert is right about the law. Congress has deliberately protected editorial discretion to prevent equal time rules from chilling political speech. And the FCC has extended this privilege to shows like his.

To understand why, you have to go back to 1959 and to a forgotten fight over the role of broadcasting in a democratic society.

Because the airwaves have been viewed as a scarce public resource, radio and television broadcasting have been regulated to balance the First Amendment rights of the press with public interest obligations. That includes the need to provide reasonable access to the airwaves for candidates for office – so citizens can hear what they have to say, whether in the form of paid advertising or unpaid news coverage.

After first appearing in the Radio Act of 1927, the equal time provision was codified in Section 315 of the Communications Act of 1934.

That law created the FCC and still governs the use of the nation’s airwaves today. It requires broadcast licensees to provide “equal opportunities” to legally qualified candidates in a given election if they allow one candidate to “use” their facilities. The requirement was intended to prevent broadcasters from favoring one candidate over another and to foster robust political debate that would serve the public interest.

But the statute did not clearly define what counted as a “use.”

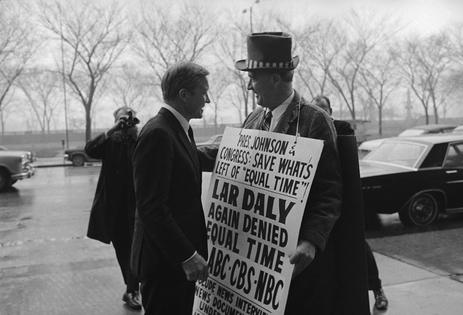

That ambiguity was a known issue, but it came to a head in 1959, when Lar Daly, a fringe Chicago mayoral candidate, filed a complaint with the FCC. He argued that if stations aired news clips of his opponents – including the incumbent mayor – as part of their routine coverage, he was entitled to equal time on air.

The FCC agreed. And it created a ruling that meant even routine news coverage of a candidate could trigger equal time obligations.

Broadcasters immediately warned that the decision would make political journalism nearly impossible. If every news interview or campaign clip required providing comparable time to every rival – including minor or fringe candidates – stations would either have to book everyone or drastically scale back political coverage.

NBC president Robert Sarnoff issued a thinly veiled threat in a message that was not lost on politicians who would be affected by the change: “Unless the gag is lifted during the current session of the Congress, a major curtailment of television and radio political coverage in 1960 is inevitable.”

Later that year, Congress stepped in and amended Section 315 to create explicit exemptions for “bona fide” newscasts, news interviews, news documentaries and on-the-spot coverage of news events. As my colleague Tim P. Vos and I note in our research on the history of the amendment, Congress rejected calls to repeal equal time altogether.

Instead, lawmakers preserved the rule for candidate-sponsored advertising while shielding news programming. Persuaded by broadcasters, lawmakers determined that professional journalism, guided by norms of balance and fairness, would best serve democratic discourse.

In signing the 1959 legislation, President Dwight D. Eisenhower highlighted the “continuing obligation of broadcasters to operate in the public interest and to afford reasonable opportunity for the discussion of conflicting views on important public issues.”

Eisenhower concluded by appealing to the good intentions of the nation’s broadcasters: “There is no doubt in my mind that the American radio and television stations can be relied upon to carry out fairly and honestly the provisions of this Act without abuse or partiality to any individual, group, or party.”

Over the decades, the FCC has interpreted the 1959 exemptions broadly.

Programs ranging from Meet the Press to The Jerry Springer Show to The Tonight Show and other interview-based broadcasts have been treated as “bona fide news interviews,” even when hosted by comedians. That’s why Colbert’s claim that there is no enforcement history against late-night talk shows is accurate.

It’s important to remember that equal time still applies in other contexts. If a candidate purchases or receives airtime for an advertisement, opponents are entitled to comparable access.

Equal time also applies to non-exempt entertainment programming, such as Saturday Night Live. Donald Trump’s hosting gig on SNL in November 2015 triggered an equal time request from four opposing primary candidates. And NBC obliged by providing a comparable amount of airtime for their campaign messages.

FCC Chairman Brendan Carr recently signaled he was considering eliminating the talk-show exemption, arguing that some programs are “motivated by partisan purposes.”

As of now, no legal change has occurred. And it seems to me that CBS has acted out of caution, responding to political and regulatory pressure rather than to an actual rule change. That makes this episode unusual: The equal time rule was perhaps applied indirectly, through corporate self-censorship, not through direct FCC enforcement.

Either way, the Colbert incident highlights the growing restrictions on editorial independence during the second Trump administration – either imposed by government threat or corporate fear.

Whether through direct regulatory intervention or indirect corporate influence, this incident and others like it show an increased willingness to interfere with the editorial independence of media producers.

The dispute is part of what some critics view as an ongoing effort by the Trump administration to silence criticism. Trump is no fan of Colbert and has targeted comedians before.

CBS already announced in 2025 that Colbert’s show will be canceled in May 2026, leading many to suggest CBS was trying to appease Trump and his FCC, particularly ahead of a then-pending merger that required FCC approval.

The 1959 amendment that created the equal time exemption aimed to preserve editorial independence and protect free expression by limiting equal time claims and ensuring vibrant political discourse. The decision reflected a judgment that professional editorial discretion, not mandatory equivalence, best served citizens.

If the FCC alters the exemption, it would represent a major shift in U.S. media policy and would almost certainly face legal challenges. The government has an important role to play in promoting free expression and protecting free speech, but this is a good time to be wary of efforts to alter regulations to control content.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Seth Ashley, Boise State University

Read more:

The limits of free speech protections in American broadcasting

Why Jimmy Kimmel’s First Amendment rights weren’t violated – but ABC’s would be protected if it stood up to the FCC and Trump

TrumpRx, Trump Kennedy Center, Trump National Parks passes − government free speech allows the president to name things after himself

Seth Ashley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments