Why UnitedHealth's Medicare Advantage program is under attack

Published in Business News

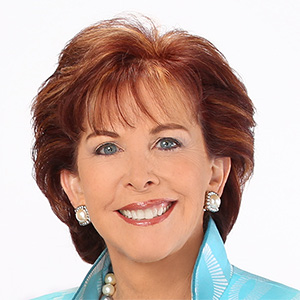

During a regular office visit, one of Dr. Nancy Keating’s patients mentioned that a UnitedHealth Group representative had recently dropped by her home.

The sixty-something patient belonged to a Medicare Advantage plan run by UnitedHealth. Insurers commonly make such house calls on seniors, but Keating was troubled by the company’s medical review.

UnitedHealth’s assessment included serious medical diagnoses that the patient — referred to as “Mrs. G” in a medical journal article by Keating — didn’t have, like diabetes.

“I was just beyond myself. I’m like, how could they do this?” the Boston physician and Harvard University professor said in an interview about the December 2023 incident. “It was just wrong.”

Adding medical conditions to a Medicare Advantage patient’s records can pull in higher federal payments to insurers while draining money from the taxpayer-supported insurance program. The system is supposed to compensate insurers for covering patients with more complex health conditions.

Yet for more than a decade, alleged diagnostic “upcoding” in Medicare Advantage has led to tens of billions of dollars in suspected overpayments to health insurers at the expense of taxpayers, according to numerous government reports and academic studies.

From the start, Eden Prairie, Minnesota-based UnitedHealth Group and its industry-leading health insurance arm, UnitedHealthcare, has been at the center of the controversy.

In July, UnitedHealth confirmed a U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation into its Medicare business. The company is cooperating with both the civil and criminal probes, while saying it stands behind the integrity of its programs.

Allegations that UnitedHealth has been particularly adept at using aggressive and questionable diagnostic coding practices to win billions in extra Medicare dollars have also come from two sets of federal watchdog findings, two recent research reports and a decade’s worth of media investigations.

A long-running federal whistleblower suit, which the DOJ joined as a plaintiff against UnitedHealth in 2017, has a critical hearing scheduled for November. A judge in California is then expected to rule on whether to throw out the case for lack of evidence.

UnitedHealth Group insists its patients have more health problems. This elevates its “risk-coding” scores — the industry metric that drives higher payments. The company said in an email response to the Minnesota Star Tribune that this is not a sign of overpayments, but simply reflects how the Medicare Advantage process works.

Alleged overpayments to Medicare Advantage insurers like UnitedHealth apparently have been growing.

From 2016 to 2020, the government made extra coding-based payments to Medicare Advantage insurers worth about $36 billion, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) estimates. Those extra payments are projected to hit $166 billion for the period of 2021 through 2025.

UnitedHealth says it’s not being overpaid by Medicare and disputes the accuracy of MedPAC estimates, which are often cited by critics.

Payments are reinvested to provide medical and ancillary benefits while keeping premiums low and “are not simply earnings for the company,” the insurer said.

“Medicare Advantage plans are doing exactly what the program was designed to do — meet the government’s objective of delivering better health outcomes and lower costs for seniors,” the company said. “As it relates to accusations about our business practices, they remain just that: baseless accusations.”

Medicare Advantage has been lucrative for health insurers — more so, at times, than the insurance offered through employers’ health plans. It’s also popular with consumers.

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage has soared from 19% of all Medicare beneficiaries in 2007 to 54% this year, according to KFF, a health care research group. The Congressional Budget Office projects Medicare Advantage’s enrollment share may hit 64% by 2034.

Enrollees in Medicare Advantage typically pay lower out-of-pocket costs than in traditional Medicare while tapping extra benefits like vision, dental and hearing care. Monthly premiums for Advantage plans generally cost less than original Medicare plus the often-used “supplemental” plans that cover coinsurance and copayment fees in the traditional program.

UnitedHealth accounts for 29% of the national Medicare Advantage market, which is 12 percentage points more than its nearest competitor, according to KFF.

Medicare Advantage was designed to save the federal government money. Unlike in original Medicare, private insurers would compete and negotiate aggressively with health care providers, driving costs down.

But in 2025, Medicare Advantage is projected to cost taxpayers about 20% more — or $84 billion — than if those members had been in original Medicare, according to MedPAC, an independent Congressional agency.

MedPAC estimates roughly half the extra spending stems from “coding intensity.” This is the tendency for insurers to add more medical conditions to a Medicare Advantage patient’s file than happens with comparable patients in original Medicare.

Brown University health economist David Meyers said while fraud and actual patient complexity may drive some coding intensity in Medicare Advantage, the biggest driver is likely insurance companies “gaming” the system.

For example, insurers may review charts for evidence that legally boosts the patient’s disease severity, even if it’s beyond what primary care providers report. Or they may enlist health care providers to get test results pointing to ailments that may not matter in terms of symptoms or the cost of care.

As a result, “Medicare Advantage beneficiaries appear to be much sicker in a way that doesn’t necessarily seem credible,” Meyers said.

Most upcoding may not be illegal, but it’s wasteful and unwise, said Dr. Don Berwick, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services during the Obama administration.

“It was taking public money and putting it in the pockets of insurers,” Berwick said.

In original Medicare, the government pays clinics and hospitals a fee after every medical service, whether it’s an X-ray or heart surgery.

But health experts argued this “fee for service” system created incentives to waste money on duplicative and unnecessary care.

With Medicare Advantage, the government sought to discourage waste by paying insurers a fixed amount per enrollee, regardless of the care provided. But since fixed payments could push insurers to avoid covering sicker and more expensive patients, the government agreed to pay Medicare Advantage plans extra for those with more documented health problems.

For example, MedPAC says an 80-year-old man in typical health in the program may have prompted the government to pay $6,726 to cover his health care costs in 2022.

When his health plan submits data showing he has diabetes without complications, the payment grows by $1,284, MedPAC wrote in March. Additional coding for vascular disease brings in $3,620 more, raising his total to $11,630. The insurer keeps the money even if the patient isn’t treated for either condition.

That’s how Medicare Advantage incentivizes insurers to report as many codes as possible.

Keating, the Boston physician, suspected upcoding in UnitedHealth’s home health assessment of Mrs. G.

Mrs. G. had been diagnosed by the insurance company’s clinician with chronic pain, morbid obesity and Type 2 diabetes with complications for cataracts and a type of nerve damage called polyneuropathy.

In Keating’s diagnosis, Mrs. G had a relatively common spinal malady, but without pain. She was obese, but not morbidly so. She did not have cataracts or polyneuropathy. And while testing put Mrs. G in the pre-diabetic range, she did not have diabetes.

UnitedHealth said it could not respond directly to Keating’s account. But the company said most diagnoses made during in-home visits are not used to generate payments.

“During a five-year period, government auditors validated roughly 90% of the conditions for which (UnitedHealthcare) was paid — much higher than other large MA plans," UnitedHealth said.

Critics have faulted many health insurers for questionable tactics in allegedly exploiting the Medicare Advantage program.

But UnitedHealth Group leads the pack, according to recent reports from the Office of Inspector General (OIG) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The federal group’s most recent report, released last October, found patients deemed sicker than average may not have received treatments for serious conditions documented in insurers’ Medicare Advantage assessments.

The OIG noted insurers’ in-home assessments may be more vulnerable to misuse because they aren’t conducted by patients’ own health care providers.

The watchdog group called on the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), to restrict the use of diagnoses based solely on in-home assessments.

Health risk assessments — often conducted in seniors’ homes — can improve health care for Medicare Advantage enrollees by opening the door to needed services, senior OIG analyst Jacqualine Reid said in an interview.

“But too often we see that these companies are using these tools to boost their payments from CMS,” she said, “and we do not see evidence of care for enrollees for the diagnoses coming from these sources.”

UnitedHealth Group maintains the OIG report was wrong. The watchdog agency published similar findings four years ago, which UnitedHealth also rejected as misleading and inaccurate at the time.

University of California San Diego public health professor Richard Kronick, who has long chronicled the Medicare Advantage payment system, analyzed Medicare data and found higher risk scores due to greater coding intensity.

This led to $33 billion in additional payments in 2021 with UnitedHealth accounting for 42% of those additional payments — considerably higher than its 27% share of the market.

“United is more aggressive in coding than any of the other five largest insurers,” Kronick said in an interview.

Brown University’s Meyers has found that while other insurers also code aggressively, UnitedHealth has the most beneficiaries, so it has the biggest impact.

The DOJ has been probing UnitedHealth’s Medicare Advantage business since at least 2017, when it joined the California whistleblower suit originally filed in 2011 by Benjamin Poehling, a former UnitedHealth Medicare finance director.

The case alleges UnitedHealth presented the government with false or fraudulent claims. The company allegedly avoided its obligation to repay significant sums by not correcting errant diagnostic codes that would have lowered its payments.

The DOJ was dealt a major blow in that case last March, when a court-appointed special master found the government lacked “any evidence” to support key elements of its complaint, concluding “there simply was no fraud.”

After a hearing in November, the federal judge is expected to rule on the recommendation to close the long-running case.

Whatever the court decides, UnitedHealth will remain central in debates over fixing risk adjustment.

The “manipulability” of the current system is a massive problem that exacerbates Medicare’s financial challenges and distorts competition among health plans, said Dr. J. Michael McWilliams, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School.

But a crackdown poses a dilemma: while alleged overpayments help drive higher profit for insurers, they also fund the benefits that make Medicare Advantage popular with consumers.

“If you cut it entirely, and get rid of all the overpayment, then there’s going to be a sizeable loss of valuable coverage,” he said. “That’s the pickle we’re in right now.”

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments